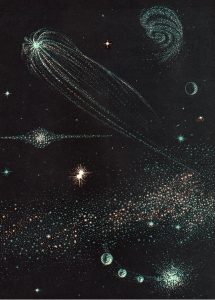

This week’s featured comet: The Great Easter Comet of 1066.

The Great Easter Comet of 1066–also called “The Comet of the Conquest”–was actually Halley’s Comet, making one of its 76-year periodic appearances. And 1066, you’ll remember from history class, was the year of the Norman Conquest of England.

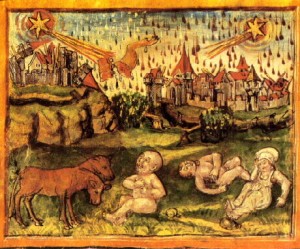

Legend says that the comet appeared at Easter time and shone for forty days, waxing and waning with the moon:

“Under its seven rays, that year, William the Conqueror felt inspired to fall upon England, while Harold, the Saxon, on the other hand, saw in the Comet a star of dread foreboding and of doom.”

The comet lit the Normans’ trip across the English Channel, and William pointed it out to his soldiers to stir their courage, saying it was a sign from heaven of their coming victory.

Sigebert of Brabant, a Belgian chronicler of the time, wrote of the comet: “Over the island of Britain was seen a star of a wonderful bigness, to the train of which hung a fiery sword not unlike a dragon’s tail; and out of the dragon’s mouth issued two vast rays, whereof one reached as far as France, and the other, divided into seven lesser rays, stretched away towards Ireland.”

After the Norman Conquest, the comet was immortalized in the Bayeux Tapestry, sewn by William’s wife, Queen Matilda, and her court. You can still see the tapestry in Bayeux, France. In one panel, King Harold of England is shown cowering on his throne while his people huddle together in fear, pointing at the comet. The Latin legend over the picture reads “Isti Mirant Stella”: They marvel at the star.

One result of the Norman Conquest (and of the comet, you could say) is that we now have many, many words of French origin in the English language, such as “conquest,” “origin,” and “language.”