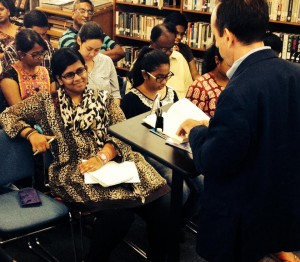

With two members of the brilliant BR Book Club. What a smart, insightful group. It’s readers like these who make me proud to be a writer.

The Night of the Comet

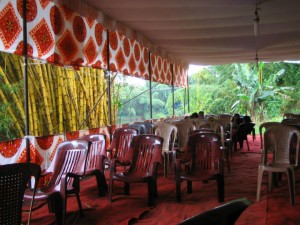

Photos from the South India Writers’ Ensemble Festival in Kerala

The river tent before the reading:

Poets doing poetry:

Me hawking my book:

With superstar author Preeti Shenoy, writer/director Punkaj Dubey, and mythologist Vani Mahesh:

The writers collective at SIWE this year:

(Standing) Mithra Venkatraj, Preeti Shenoy, Manjiri Prabhu, Shinie Antony, Vani Mahesh, Saniya, Ambai, Malsawmi Jacob, Jayasree Kasaravally and Tulasi Venugopal.

(Below) Yuvan Chandrashekar, S Diwakar, George Bishop, Pankaj Dubey and Anjali Purohit.

We Are Stardust, We Are Golden

Nice piece by astronomer Ray Jayawardhana in yesterday’s New York Times, “Our Cosmic Selves.” He opens with the line from the Joni Mitchell song that provided me with the epigraph for THE NIGHT OF THE COMET:

Nice piece by astronomer Ray Jayawardhana in yesterday’s New York Times, “Our Cosmic Selves.” He opens with the line from the Joni Mitchell song that provided me with the epigraph for THE NIGHT OF THE COMET:

“We are stardust, we are golden,

We are billion-year-old carbon,

And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

He goes on to discuss how we are all, indeed, made of “star dust”:

“By now, ‘stardust’ and ‘star-stuff’ have nearly turned cliché. But that does not make the reality behind those words any less profound or magical: The iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones and the oxygen we breathe are the physical remains — ashes, if you will — of stars that lived and died long ago.”

Here’s the whole piece, for your reading and intellectual pleasure this Easter weekend. Enjoy!

Our Cosmic Selves

APRIL 3, 2015

By RAY JAYAWARDHANA

JONI MITCHELL beat Carl Sagan to the punch. She sang “we are stardust, billion-year-old carbon” in her 1970 song “Woodstock.” That was three years before Mr. Sagan wrote about humans’ being made of “star-stuff” in his book “The Cosmic Connection” — a point he would later convey to a far larger audience in his 1980 television series, “Cosmos.”

By now, “stardust” and “star-stuff” have nearly turned cliché. But that does not make the reality behind those words any less profound or magical: The iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones and the oxygen we breathe are the physical remains — ashes, if you will — of stars that lived and died long ago.

That discovery is relatively recent. Four astrophysicists developed the idea in a landmark paper published in 1957. They argued that almost all the elements in the periodic table were cooked up over time through nuclear reactions inside stars — rather than in the first instants of the Big Bang, as previously thought. The stuff of life, in other words, arose in places and times somewhat more accessible to our telescopic investigations.

Since most of us spend our lives confined to a narrow strip near Earth’s surface, we tend to think of the cosmos as a lofty, empyrean realm far beyond our reach and relevance. We forget that only a thin sliver of atmosphere separates us from the rest of the universe.

But science continues to show just how intimately connected life on Earth is to extraterrestrial processes. In particular, several recent findings have further illuminated the cosmic origins of life’s key ingredients.

Take the element phosphorus, for example. It is a critical constituent of DNA, as well as of our cells, teeth and bones. Astronomers have long struggled to trace its buildup through cosmic history, because the imprint of phosphorus is difficult to discern in old, cool stars in the outskirts of our galaxy. (Some of these stellar “time capsules” contain the ashes of their forebears, the very first generation of stars that formed near the dawn of time.)

But in a paper published in December in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, a research team reported that it had measured the abundance of phosphorus in 13 such stars, using data taken with the Hubble Space Telescope. Their findings highlight the dominant role of so-called hypernovae, explosions even more energetic than supernovae that spell the demise of massive stars, in making the elements essential for life.

More than just atoms were produced in the celestial realm. Growing evidence suggests that interstellar space was also where atoms united to make some molecules pertinent for life. A study published last fall in Science, for example, used computer simulations to establish the provenance of Earth’s water. Its surprising verdict: Up to half the water on our planet is older than the solar system itself. Ancient water molecules assembled in the chilly confines of a gigantic gas cloud. That cloud spawned our sun and the planets that orbit it — and somehow those ancient water molecules survived the perils of the planetary birth process to end up in our oceans and, presumably, our bodies.

Such interstellar clouds may have been well suited for brewing a multitude of molecules. Last fall, in another study published in Science, a research team reported the first discovery in a stellar nursery of a carbon-bearing molecule with a “branched” structure. The detection of this molecule, the researchers wrote, “bodes well” for the presence in interstellar space of amino acids, for which a branched structure is a defining feature. (The researchers made use of a vast, partially operational network of radio dishes being erected on a high-altitude plateau in northern Chile, whose location makes it easier for radio emissions to reach us from the coldest bits of the galaxy, where the alchemy of life is presumed to have begun.)

Astrochemists are excited by this discovery because amino acids, which have been found already in some meteorites, form the basis of proteins. Meanwhile, last month, NASA scientists reported the creation of key DNA components in a laboratory experiment that simulated the space environment. Together, these findings raise the odds that life’s building blocks were concocted in space and blended into the material that formed Earth and its planetary siblings.

Amid the material comforts and the relentless distractions of modern life, the universe at large may appear remote, intangible and irrelevant, especially to those of us who are city dwellers. But the next time you catch a glimpse of the Milky Way in its true glory, from a dark outpost far from city lights, think of those countless stars as nuclear factories and the starless hazy patches as molecular breweries. It is not much of a stretch to imagine the inchoate seeds of life emerging in the distance.

Christmas in Space

Boys watch the Christmas Eve broadcast from Apollo 8 astronauts in space, December 24, 1968. (Photo: Bruce Dale/National Geographic, via Will Amato.)

In THE NIGHT OF THE COMET, Alan Broussard and son watch a TV broadcast of the Skylab astronauts decorating a Christmas tree made out of empty space-food tubes in 1973:

Comet Siding Spring: Once in a Million Years

Astronomers are excited about Comet Siding Spring’s very close encounter with Mars this coming Sunday. Siding Spring was spotted back in January 2013. An Oort Cloud comet, it’s said to be the size of a small mountain, with a million-year orbit. A posse of spacecraft and Mars rovers are jockeying into position right now to observe it. Here on Earth, the comet will be visible with binoculars in the Southern Hemisphere.

How close will Comet Siding Spring come to Mars? 83,000 miles–which in space distances is a hair’s breadth, about a third of the distance between here and the Moon. Last year, before they’d plotted out its trajectory, astronomers were genuinely worried that the comet might hit Mars.

Its trajectory is such that it’ll never get closer to the Earth than some 83 million miles, so no need to panic yet. Of course, passing that close to Mars, there’s a possibility that Siding Spring might upset the Red Planet’s orbit, throwing the whole solar system out of whack, in which case, well . . . Best not to think about that.