Okay, so maybe you’re not that crazy about comets, but I promise you’ll like No. 5 in our Comet of the Week: the famous Cheseaux’s Comet of 1744, or, as I like to call it, The Great Singing Comet.

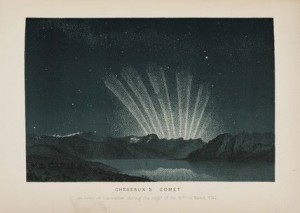

What distinguishes this comet, spotted in late 1743 by, among others, the Swiss astronomer Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux, was its remarkable six-rayed tail.

“The comet arrived at perihelion on March 1 by which time it was bright enough to be observed in daylight with the naked eye. After perihelion a spectacular multiple tail developed which rose well above the morning horizon, in a dark sky while the head was still well below that same horizon. The tail formed a giant fan comprised of six multiple tails. While astronomers were familiar with comets having two tails (a straight gas or ion tail and a curved dust trail), one with six was something completely different.” (From Hunting and Imaging Comets, by Martin Mobberley, 2011.)

But wait! It gets better: Cheseaux’s comet made noise. Yes. Chinese astronomers, who also observed it, reported hearing sounds issuing from the comet. I like to imagine it as a kind of singing:

“Mysteriously, some of the Chinese records of this comet describe atmospheric sounds when the object was at its peak. In an era when there were no planes or cars how can this be explained? Maybe the sounds were distant animals howling in terror at the sight of such an awesome spectacle?” (Mobberly.)

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology offers this possible explanation for sounds emanating from falling stars and comets:

“This was one of closest cometary approaches on record. If the comet’s charged particles or magnetic field interacted with the magnetosphere, VLF waves may have been generated to produce electrophonic sounds at ground level.”

There you have it.

After the nights of March 7-8, Cheseaux’s Comet was never seen, or heard from, again. But it achieved such great and flashing fame that for a time it appeared on German coins.