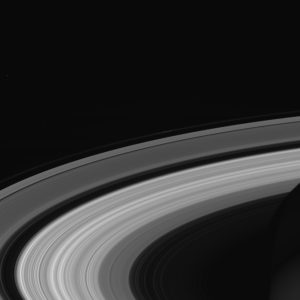

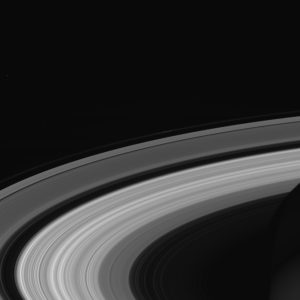

Saturn’s rings captured by Cassini on Wednesday. Credit NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

CASSINI VANISHES INTO SATURN, ITS MISSION CELEBRATED AND MOURNED

New York Times

By KENNETH CHANG

SEPT. 14, 2017

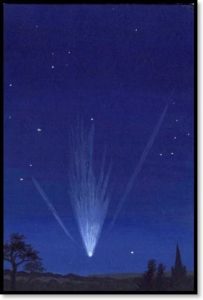

PASADENA, Calif. — NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, the intrepid robotic explorer of Saturn’s magnificent beauty, ended a journey of 20 years on Friday like a shooting star streaking across Saturn’s sky.

By design, the probe vanished into Saturn’s atmosphere, disintegrating moments after its final signal slipped away into the background noise of the solar system. Until the end, new measurements streamed one billion miles back to Earth, preceded by the spacecraft’s last picture show of dazzling sights from around our sun’s sixth planet.

“The signal from the spacecraft is gone and, within the next 45 seconds, so will be the spacecraft,” Earl Maize, the program manager, announced in the control room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory here, just after 4:55 a.m. local time.

His eyes teared and his voice wavered as he said, “I am going to call this the end of mission.” During a news conference later, he said, “To the very end, the spacecraft did everything we asked.”

The team members, some of whom had spent decades on the mission, started hugging each other when news of the spacecraft’s demise arrived.

Never again would Cassini send home the images and data that inspired discoveries and wonder during the probe’s 13 years in orbit around the ringed planet.

“For me, there’s a core of sadness, in part in thinking of the breakup of the Cassini family,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist. “But it’s both an end and a beginning as these people go off and work on other things.”

The mission for Cassini, in orbit since 2004, stretched far beyond the original four-year plan, sending back multitudes of striking photographs, solving some mysteries and upending prevailing notions about the solar system with completely unexpected discoveries.

“Cassini is really one of those quintessential missions from NASA,” said Thomas H. Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science. “It hasn’t just changed what we know about Saturn, but how we think about the world.”

Cassini’s hazy origin story

Cassini had its origins in the brainstorm of two scientists, Daniel Gautier of the Paris Observatory and Wing-Huen Ip, then at the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy in Germany.

NASA’s two Voyager spacecraft flew through the Saturn system in 1980 and 1981. Voyager 1, in particular, provided a close-up look at Titan that was enthralling and maddening. Larger than the planet Mercury, Titan was enshrouded in haze. The atmosphere was thicker than Earth’s and contained methane and other carbon-based molecules. What lay below, no one knew.

“Those discoveries led to many more questions,” Dr. Ip recalled.

In 1982, Dr. Gautier and Dr. Ip proposed to the European Space Agency that it collaborate with NASA on a Saturn mission: an orbiter paired with a probe that would parachute onto Titan.

The orbiter became Cassini, built and operated by NASA; the Titan probe was named Huygens, a project of the European Space Agency. The Europeans approved Huygens in 1988. A year later, NASA gave the go-ahead for Cassini. The craft were named for a Dutch astronomer, Christiaan Huygens, who discovered Titan and figured out Saturn had rings, and Giovanni Domenico Cassini, a French-Italian astronomer, who discovered four other major moons of Saturn, each in the 17th century.

To take advantage of the gravitational boost from a flyby of Jupiter to accelerate Cassini-Huygens, the spacecraft was launched on Oct. 15, 1997.

Discovering an Earthlike alien moon

Seven years later, Cassini swung into orbit around Saturn. A few months later, Huygens headed to its rendezvous with Titan, the first attempt to touchdown on a moon other than our own.

The lander was equipped with instruments to identify molecules in the air, measure the winds and haze, and take pictures on the way down.

Because the spacecraft designers did not know what the surface was made of, they had designed Huygens to handle several possibilities, including floating for a few minutes if it had turned out that Titan’s surface was a global ocean of methane.

Instead, Huygens bumped onto solid ground, surrounded by a complex network of small rivers. “If you would jump from your table or your desk, you would land on the floor at this speed,” said Jean-Pierre Lebreton, the project scientist for Huygens. “A very reasonable landing speed.”

Photographs at the surface showed what looked like rounded cobblestones that turned out to be blocks of water ice.

The data from Huygens, together with that gathered by Cassini in repeated flybys, revealed Titan as a world shaped by active geological processes with rivers, lakes and rain. But in the frigid temperatures there, about minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit, the fluid is not water, but methane. “Titan has really revealed an Earthlike world,” Dr. Lebreton said.

A journey toward disintegration

NASA spacecraft, if they survive to their destination, often just keep going.

Cassini stayed seven more years to watch changes in Saturn through the passing of seasons. It takes Saturn 29.5 years to orbit the sun, so Cassini has been there for almost half a Saturn year.

One of the mission’s most surprising discoveries was an ocean of water beneath the icy exterior of Enceladus that may be heated by hydrothermal vents similar to those at the bottom of oceans on Earth. The water on this moon and the carbon compounds it contains are some of the key ingredients needed for life that scientists would have thought unlikely on a moon just 313 miles wide.

Even at the end, 20 years after launch, Cassini and its instruments remained in good working shape. The plutonium power source was still generating electricity. But there was not enough propellant fuel left to safely send Cassini anywhere except into Saturn.

Any spacecraft, even one launched two decades ago, has unwanted microbial hitchhikers aboard. In particular, planetary scientists wanted to ensure that there was zero chance of the spacecraft crashing into and contaminating Enceladus or Titan, which could also be hospitable for life. And NASA wants to leave the Saturn system pristine.

In the very last phase of the mission, Cassini dove through the gap between Saturn and the planet’s innermost ring. That provided new, sharp views of the rings and allowed the craft to probe the planet’s interior, as another NASA spacecraft, Juno, is doing at Jupiter.

The last photographs taken by Cassini started streaming back to Earth on Thursday. An infrared image marked the spot high above the planet’s cloud tops where Cassini would disintegrate hours later.

Once these had been sent back to Earth, the probe was reconfigured for the final plunge.

Usually, Cassini would make observations, store them in its memory and beam them back to Earth later. This time, there would be no later. Instead, on the final plunge, the spacecraft kept its antenna dish pointed at Earth, as its instruments gave scientists their deepest direct look ever into Saturn.

As it moved into Saturn’s atmosphere, the drag of gas molecules started twisting the spacecraft, and its small thrusters could no longer keep the 30-passenger school bus-sized craft upright.

Cassini tipped over, its antenna no longer pointing at Earth. That is when the signal disappeared, at an altitude of about 870 miles.

The spacecraft disintegrated at about 7:31 a.m. Eastern time, and much of it melted quickly. The most resilient bits were probably the casings around its plutonium power source, designed to withstand re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere or an explosion at launch.

Studying final signals

Dr. Ip, who helped propose the mission in the 1980s, flew from Taiwan, where he is now a professor at National Central University, to join a commemoration of Cassini’s end at the California Institute of Technology. Hundreds of people gathered for what was part reunion, part celebration, part wake. In the predawn hours of Friday, he and his family were watching the mission’s final moments on giant screens placed on the lawn.

When the signal disappeared, Dr. Ip’s daughter, Anita, cried and hugged her father. “It’s hard to explain,” she said. “It’s always been part of the family.”

Dr. Ip himself was more stoic and bemused. How was he feeling?

“Oh, fine,” he said.

Not far away, William S. Kurth, a University of Iowa physicist who oversaw one of Cassini’s scientific instruments, was looking at a brightly colored plot on his laptop. The final data had already made the journey from Saturn to Australia to Pasadena to Iowa and back again to his computer on the lawn. He pointed out the radio emissions Cassini measured as it had entered Saturn’s atmosphere.

It was less than 10 minutes after word of Cassini’s death, and Dr. Kurth had homework to do.