No. 6 in our Comet a Week is The Great Comet of 1811, also known as Napoleon’s Comet. With a coma over a million miles across, it was visible in the sky for almost a year. The comet was believed to have portended Napoleon’s invasion of Russia and the War of 1812.

The best thing about this comet is that it makes a cameo in Count Leo Tolstoy’s magnificent War and Peace, where it’s called, confusingly, the Comet of 1812.

It appears at the end of Book Eight (in my Kropoktin translation). Pierre has just confessed his love to Natasha. Here’s the passage:

“Where now?” asked the driver.

“Where?” repeated Pierre to himself. “Where can I go now? To the club, or to make some calls?”

All men, at this moment, seemed to him so contemptible, so mean, in comparison with the feeling of emotion and love that overmastered him–in comparison with that softened glance of gratitude which she had given him just now through her tears.

“Home,” said Pierre, throwing back his bearskin cloak over his broad, joyfully throbbing chest, though the mercury marked ten degrees of frost.

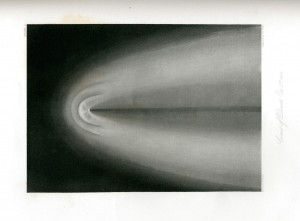

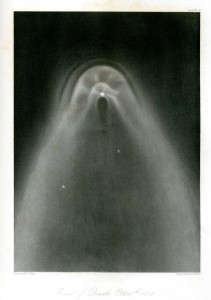

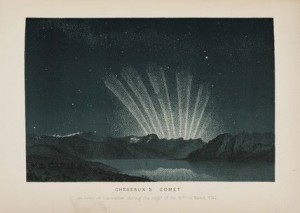

It was cold and clear. Above the dirty, half-lighted streets, above the black roofs of the houses, stretched the dark, starry heavens. Only as Pierre gazed at the heavens above, he ceased to feel the humiliating pettiness of everything earthly in comparison with the height to which his soul aspired. As he drove out of Argat Square, the mighty expanse of the dark, starry sky spread out before his eyes. Almost in the zenith of this sky–above the Pretchistensky Boulevard–convoyed and surrounded on every side by stars, but distinguished from all the rest by its nearness to the earth, and by its white light, and by its long, curling tail, stood the tremendous brilliant comet of 1812–the very comet that men thought presaged all manner of woes and the end of the world.

But in Pierre, this brilliant luminary, with its long train of light, awoke no terror. On the contrary, rapturously, his eyes wet with tears, he contemplated this glorious star which seemed to him to have come flying with inconceivable swiftness through measureless space, straight toward the earth, there to strike like an enormous arrow, and remain in that one predestined spot upon the dark sky; and, pausing, raise aloft with monstrous force its curling tail, flashing and sparkling with white light, amid the countless other twinkling stars. It seemed to Pierre that this star was the complete reply to all that was in his soul as it blossomed into new life, filled with tenderness and love.

I think we can all agree that no one writes comets like Tolstoy.