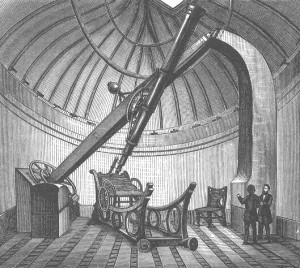

Came across this a while I was researching comets and such last year, “George Bishop’s Observatory.” I especially like that sled-like recliner on rails, for watching the stars. That’s exactly what I would want for my observatory:

Here’s the Wikipedia entry on George Bishop’s Observatory, in case you’re curious:

George Bishop’s Observatory was an astronomical observatory erected in 1836 by the astronomer George Bishop near his residence at the South Villa of Regent’s Park, London. It was equipped with a 7-inch (180 mm) Dollond refractor. It is assigned number 969 in the International Astronomical Union’s list of observatories.

The Reverend William Rutter Dawes conducted his noted investigations of double stars at the observatory from 1839 to 1844; John Russell Hind began his career there in October of the following year. From the time that Karl Ludwig Hencke’s detection of Astræa, 8 Dec. 1845, showed a prospect of success in the search for new planets, the resources of Bishop’s observatory were turned in that direction, and with conspicuous results. Between 1847 and 1854 Hind discovered ten small planets at the observatory, and Albert Marth one. Other notable astronomers to use the observatory included Eduard Vogel, Charles George Talmage, and Norman Robert Pogson.

The observatory closed when Bishop died in 1861, and in 1863 the instruments and dome were moved to the residence of George Bishop, junior, at Meadowbank, Twickenham, where a new observatory was constructed to follow the same system of work. Twickenham Observatory closed in 1877 and the instruments were given to the Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte in Italy.Regent’s College London now stands on the site of the observatory.

And here’s this from the Wikipedia entry on George Bishop, Astronomer:

In 1836 Bishop was able to realise a long-held intention by erecting an astronomical observatory near his residence at the South Villa of Regent’s Park, on which he spared no expense in order to ensure that it would be of practical use. “I am determined,” he said when choosing its site, “that this observatory shall do something.”

A testimonial was awarded to Bishop by the Royal Astronomical Society in 1848 “for the foundation of an observatory leading to various astronomical discoveries” and presented to him with a warmly commendatory address by Sir John Herschel. . . .

After a long period of physical but not mental illness, Bishop died on 14 June 1861 at the age of 76.

I like his quote, so much so that I’ll repeat it here:

“I am determined,” he said when choosing its site, “that this observatory shall do something.”