Thanks to Andi Russell of The Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, Va.) for a glowing review of The Night of the Comet.

I’m honestly impressed when a reviewer can so neatly sum up a book and say “This is what it’s about,” as Russell does here. I know myself from trying to write book descriptions–of my own books, even!–how difficult this can be.

Sept. 1, 2013

Dad’s Head is in the Stars

BY ANDI RUSSELL/THE FREE LANCE–STAR

AUTHOR George Bishop paints an intimate portrait of an unraveling family as Comet Kohoutek comes crashing through their lives in his second novel, “The Night of the Comet.”

This nostalgic and heart-achingly relatable tale is told from the perspective of a high school freshman growing up in southern Louisiana in 1973.

Fourteen-year-old Alan Broussard Jr., or “Junior,” is experiencing his first serious crush. But just as he begins to navigate the mysteries of the heart, he starts to glean from his parents that love isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Junior and the rest of his family’s conflicting feelings of hope and disappointment are prevalent through much of the story.

Junior’s dad, Alan Sr., is a high school science teacher whose fascination with what scientists are calling “the comet of the century” embarrasses Junior and his older sister, Megan. As Kohoutek gets closer, though, anticipation starts to build throughout the small town. Alan becomes a local celebrity of sorts, and the comet demands more and more of his time.

During the evenings, Junior looks out of his new telescope (a birthday gift from his dad) across the canal and into the home of his crush, Gabriella, and her high-society family. The new neighbors have also caught the attention of Junior’s mother, Lydia, an already-restless housewife who has always dreamed of a glamorous life.

Bishop’s lovely prose will likely bring readers to empathize with each member of the Broussard family. They will feel Junior’s confusion, Megan’s impatience, Lydia’s unhappiness and Alan’s isolation.

Part coming-of-age story, part family saga, “The Night of the Comet” is sweet and sad, heartbreaking and uplifting. It also provides a wealth of information on astronomy and the stars. The night sky looms in the background, like another character in the story.

Occasional and avid stargazers alike should relish Bishop’s take on the coming of Comet Kohoutek and how it affected one small town.

The release of the novel is timely, as many astronomy enthusiasts are currently tracking sun-approaching Comet ISON, which some reporters have already dubbed “the comet of the century.”

The scientific community appears to believe it is too soon to tell whether ISON will dazzle or be a dud. After reading this book, I know I will be paying close attention.

Andi Russell is a designer with The Free Lance–Star.

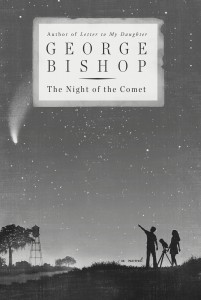

THE NIGHT OF THE COMET

By George Bishop

(Ballantine Books, $25, 316 pp.)