Birmingham, Nazis, and Comets: A Short Photo Essay

One free morning while I was in Birmingham, Ala., on my book tour for THE NIGHT OF THE COMET, I took a stroll out of my hotel to visit the Birmingham Museum of Art. (It’s an excellent museum, by the way, and well worth the visit if you’re ever in Birmingham.)

To get to the museum, I walked past the downtown Jefferson County Courthouse, and was struck by something I saw carved into the marble pedestals on either side of the rear entrance of the courthouse:

A closer look:

That’s right, those are swastikas, infamously associated with Nazis and Nazism since the National Socialist German Workers Party adopted the swastika as their official symbol in 1920. As in:

And:

But what were swastikas doing on the Birmingham courthouse? What could they signify here?

Historically, Alabama, like my own native Louisiana, has not exactly been known as a model of racial tolerance and diversity.

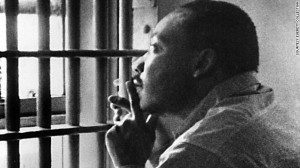

See, for example, Martin Luther King, Jr., in the Birmingham jail:

Or Alabama state troopers attacking civil-rights demonstrators during the Selma to Montgomery march on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965:

Or Birmingham police fire-hosing black high schools students:

You get the idea.

Even today, Alabama harbors white supremacy groups–30 “active hate groups,” according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The Council of Conservative Citizens, for example, has chapters in Birmingham, Montgomery, Florence, Jasper, and Cullman:

The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan has chapters in at least five Alabama cities:

And there’s a chapter of the National Socialist Movement in Mobile:

(This photo is from a rally in Minneapolis, not Mobile.)

Nevertheless, it’s highly unlikely that the swastikas carved into the courthouse steps in Birmingham have anything to do with Nazism or white supremacy.

The Jefferson County Courthouse was built in 1930 by a Chicago architectural firm, and the pedestals and its swastikas were probably carved sometime in the late 20s. Prior to World War II, the swastika appeared here and there as a decorative element on public buildings and monuments all around the U.S., without any association to Nazism or Germany.

Here it is shown as a good luck symbol on an American postcard from 1907:

The swastika as a symbol has been around for millennia, dating back as far as 3000 BC, when it showed up in the Indus Valley during the Bronze Age. According to Wiki, “Swastikas have also been used in various other ancient civilizations around the world including India, Iran, Nepal, China, Japan, Korea and Europe.” They’re found in Native American culture, as well.

Today, if you travel in India, you’ll see the swastika everywhere, especially on temples; it’s used as a religious symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Like this:

The word itself, “swastika,” is from ancient Sanskrit and means, literally, “to be good.”

The question, then, is how this symbol, carved into the county courthouse in Birmingham, demonized by the Nazis, and used all over the world for centuries, came to exist in the first place? Stranger still, the symbol apparently arose spontaneously at roughly the same time in many different cultures spread very far apart, as a common representation of something, shall we say, divine. How did this happen?

Carl Sagan (1934-1996), the famous astronomer who for a couple of decades made stargazing cool, had a fascinating theory.

He proposed that the swastika symbol was inspired by a comet: a strange, great comet that was witnessed simultaneously by people all over the world, centuries ago.

He explains it (with Ann Druyan) in his 1985 book “Comet”:

“What we are imagining is something like this: It is early in the second millennium B.C. Perhaps Hammurabi is King in Babylon, Sesostris III rules in Egypt, or Minos in Crete . . . While all the people on Earth are going about their daily business, a rapidly spinning comet with four active streamers appears.”

He goes on:

“If something like it slowly materialized in your night sky amidst shrouds and fountains of dust–something self-propelled, animate, almost purposeful–you would surely find the experience noteworthy. You would speculate on its meaning, its religious significance, its portent. People would copy the symbol down so other would know about it, so that this marvel would not be forgotten. Whether you view it as an auspicious sign or as a harbinger of disaster, no one need explain to you that this thing is important.”

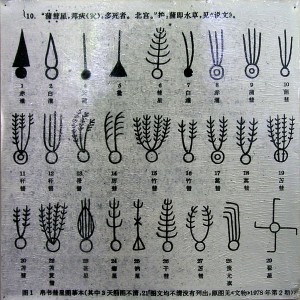

As proof, Sagan offers this ancient atlas of observed comets, from the Han Dynasty in China, third or fourth century BC, recorded by “the culture with the longest tradition of careful observation of comets.” And there it is, number 29 in a catalogue of comets, comet “Di-Xing,” “the long-tailed pheasant star”:

So there you have it. The unexpected but not completely implausible line from this:

To this:

To this:

(Apologies, by the way, to all the very kind and decent people I met while traveling in Alabama. This is not meant to be about you.)