A recent New York Times article describes a cool phenomenon that gets a mention in THE NIGHT OF THE COMET: the tons of cosmic dust that rain down on the Earth every day. 10 tons of it, every day.

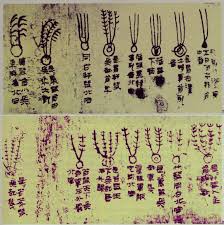

These examples of space dust found on Earth are collected in a new book, “In Search of Stardust: Amazing Micro-Meteorites and Their Terrestrial Imposters,” and were found on buildings, parking lots, sidewalks and park benches. Credit Jan Braly Kihle/Jon Larsen.

Says the article:

“The dust consists of tiny remnants from the solar system’s birth, including debris from the lumps of dirty ice known as comets and from ages of smashups among planets and the big rocks known as asteroids. While most of the particles are interplanetary in nature, some contain grains of matter from outside the solar system, or true stardust . . .

“’Your car is covered with cosmic dust,’ Dr. Brownlee said. ‘We inhale this stuff. We eat it every time we eat lettuce. But normally, it’s incredibly difficult to find.'”

The article describes how one amateur scientist finally devised a way to find and photograph all this stuff. Click on the above link in the title to read, or see the full text below.

After decades of failures and misunderstandings, scientists have solved a cosmic riddle — what happens to the tons of dust particles that hit the Earth every day but seldom if ever get discovered in the places that humans know best, like buildings and parking lots, sidewalks and park benches.

The answer? Nothing. Look harder. The tiny flecks are everywhere.

An international team found that rooftops and other cityscapes readily collect the extraterrestrial dust in ways that can ease its identification, contrary to science authorities who long pooh-poohed the idea as little more than an urban myth kept alive by amateur astronomers.

Remarkably, the leader of the discovery team — and co-author of a recent paper in Geology, a monthly journal of the Geological Society of America — turns out to be a gifted amateur who devoted himself to disproving the skeptics.

A noted jazz musician in Norway, he rearranged his life to include eight long years of extraterrestrial sleuthing. His hunt has now produced a significant discovery, a colorful book for lay readers and what scientists call a portrait gallery of alien visitors.

“I hope and believe this will start something,” the musician, Jon Larsen, said in an interview. His goal? “Making it easy.”

His book, “In Search of Stardust: Amazing Micro-Meteorites and Their Terrestrial Imposters,” due out in August, details the secret of his extraordinarily successful hunts. Its 150 pages and 1,500 photomicrographs, or photos taken through a microscope, tell how Mr. Larsen taught himself to distinguish cosmic dust from the minuscule contaminants that arise from roads, shingles, factories, roof tiles, construction sites, home insulation and holiday fireworks.

As his book puts it, “To pick out one extraterrestrial particle among billions of others requires knowledge both about what to look for and what to disregard.”

The diminutive flecks to which Mr. Larsen, 58, has devoted himself represent the smallest parts of a cosmic downpour that has lashed the Earth for billions of years.

Careful observers of the night sky are familiar with shooting stars — speeding bits of extraterrestrial rock that plunge through the Earth’s atmosphere, often burning up completely. The biggest can strike the ground, some forcefully enough to dig craters. In 2013, a relatively small rock exploded over the Russian city Chelyabinsk, releasing a shock wave that injured hundreds of people, mainly as windows shattered into flying glass.

But all that represents a tiny fraction of the downpour. Scientists say most of the cosmic material is remarkably small — barely the width of a human hair. Known as micrometeorites, they rain down on the planet more or less continuously but have proved remarkably hard to find. Some bits are so small and lightweight that they drift down to the Earth’s surface without melting.

The dust consists of tiny remnants from the solar system’s birth, including debris from the lumps of dirty ice known as comets and from ages of smashups among planets and the big rocks known as asteroids. While most of the particles are interplanetary in nature, some contain grains of matter from outside the solar system, or true stardust. Their diversity makes them excellent windows on the cosmos.

Scientists have found micrometeorites mainly in the Antarctic, remote deserts and other places far from civilization’s haze. Starting in the 1940s and 1950s, investigators tried to find them in urban areas but eventually gave up because of the riot of human contaminants.

Significantly, it turns out that specialists trying to establish the cosmic origins of the tiny specks have tended to examine their chemical signatures rather than their overall appearance. That left a large opening for Mr. Larsen.

Matthew J. Genge, one of the Geology paper’s four authors and a senior lecturer in earth and planetary science at Imperial College, London, used an electron microprobe at the Natural History Museum in London to determine the chemical makeup of Mr. Larsen’s finds and confirm their cosmic origin.

In an interview, he said that, over all, the grains that survive the atmospheric plunge and land on the Earth’s surface add up to more than 4,000 tons annually, or more than 10 tons a day. “He’s done a valuable thing in classifying the contaminants,” Dr. Genge said of Mr. Larsen’s work. “It has wide-reaching implications.”

Donald E. Brownlee, an astronomer at the University of Washington who helped establish the field, called Mr. Larsen a true citizen scientist whose work will aid the global hunt for the tiny specks.

“Your car is covered with cosmic dust,” Dr. Brownlee said. “We inhale this stuff. We eat it every time we eat lettuce. But normally, it’s incredibly difficult to find.”

Mr. Larsen came to what he calls Project Stardust as a jazz guitarist in Norway, perhaps known best as the founder of Hot Club de Norvège, a string quartet. His group helped spur the global revival of gypsy jazz.

As Mr. Larsen tells the story, he was an enthusiastic rock collector as a child but did so well as a musician that he set aside his early scientific ambitions. Then, in 2009, at a country house outside Oslo, he was cleaning an outdoor table when a bright speck caught his eye.

“It was blinking in the sunlight,” he recalled. He touched the fleck. “It was angular in some way, kind of metallic but so small — a tiny dot.”

Intrigued, Mr. Larsen suspected it was a cosmic visitor and began to look for more. He collected dust samples from Oslo and cities around the globe, moonlighting as a scientist while vacationing or touring with his jazz group. He took samples from roads, roofs, parking lots and industrial areas.

Put indelicately, he collected hundreds of pounds of dreck — sludge from drains, gutters and downspouts, the dregs of civilization that most people try to avoid.

“Still, I didn’t find a single micrometeorite,” he recalled. “It was very frustrating.”

Mr. Larsen then changed tactics. Rather than looking exclusively for cosmic dust, he taught himself how to classify the dozens of different kinds of earthly contaminants, starting a process of elimination that slowly narrowed the candidates and raised the chances that some tiny fraction of the urban debris might turn out to belong to the cosmos.

The breakthrough came two years ago. In London, Dr. Genge studied one of the gathered particles — from Norway, not Timbuktu — and confirmed that it was indeed a traveler from outer space. Mr. Larsen quickly identified hundreds more.

“Once I knew what to look for, I found them everywhere,” he said.

In the Geology paper, the scientific team reports the discovery of about 500 micrometeorites — collected mainly from roof gutters in Norway — and tells of the detailed analysis of 48 of the extraterrestrial specks. The team includes two of Dr. Genge’s students, Martin D. Suttle of Imperial College and Matthias Van Ginneken of the Université Libre in Brussels.

The team described the cosmic dust as the youngest collected to date, because gutters tend to get cleaned fairly regularly. Also, urban surfaces are recent arrivals in the global landscape compared to polar ice and ancient deserts.

In his travels, Mr. Larsen recently visited with Michael E. Zolensky, an extraterrestrial materials scientist in Houston at the Johnson Space Center of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. They not only talked shop but also went up to the roof of the large building that houses rocks from the Apollo moon program.

“It was pretty cool,” Dr. Zolensky said. “The curation building is now a collector of cosmic dust.”

In an interview, Mr. Larsen described his method — sorting through the contaminants in a process of elimination — as “something that anybody can do. It could and should become part of teachings in schools, an aspect of citizen science.”

Dr. Brownlee of the University of Washington agreed. He said that, while many schools try to find cosmic dust particles in programs meant to make science classes more inviting and accessible, few if any succeed. “It could help a lot,” he said of Mr. Larsen’s method. “For education, it’s pretty cool.”

Dr. Genge of Imperial College said Mr. Larsen’s techniques, if adopted widely, might also open a new lens on the cosmos.

The gravitational pull of the planets, he noted, appear to tug on the dust clouds of the solar system and slowly change their orbits. He said a wave of new terrestrial finds could help scientists better map the clouds, raising more questions for science about the structure of the universe.

“I consider my microscope a telescope,” Dr. Genge said. “It can give you a pretty big picture.”